Meningitis

Meningitis is a disease condition that typically affects pediatrics and young adults, so it is usually taught as part of a pediatrics course. The highest disease rates are children younger than 12 months, with the second highest occurrence being in teens and young adults age 16-23. This can further be stratified into those living in crowded conditions or tight quarters such as a college dormitory. However, it is important to note that it can occur at any age.

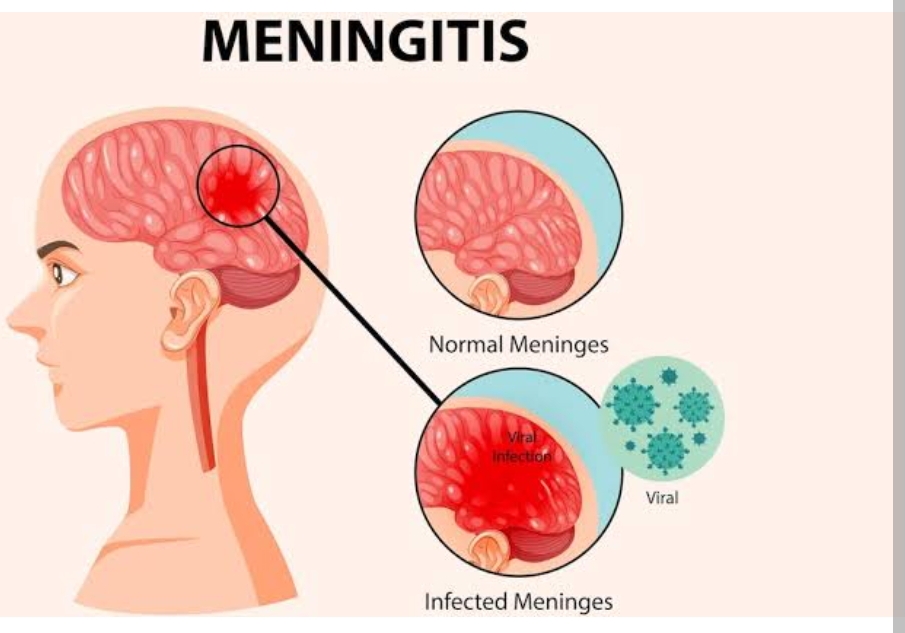

Meningitis is inflammation of the meninges, which are the outer layers surrounding the brain and spinal cord. The meninges are composed of three distinct layers – the pia mater, the arachnoid and the dura mater. The inflamed meninges can be quite painful and can lead to other neurological symptoms, which will be discussed further on.

What causes meningitis?

Meningitis is usually a result of bacterial or viral infection, but can also be due to fungal or protozoan infection as well. Of these, bacterial meningitis is the most severe. In most cases, meningitis occurs secondary to another infection such as pneumonia or sinusitis. It can also occur due to infections secondary to lumbar puncture, skull fractures or ventricular shunts. The pathogen essentially enters the system and is carried throughout the brain and spinal cord tissues by the CSF.

What are the different types of meningitis?

Viral meningitis – This is the most common form of meningitis and is usually less severe than the bacterial form. It is most often caused by enteroviruses, but can also be related to chicken pox, measles, mumps, rubella, and bites from insects such as mosquitos. It can be spread person-to-person through fecal contamination, so it’s important to teach patients to thoroughly wash hands after using the bathroom or changing a baby’s diaper. Vaccination against measles, mumps, chicken pox and rubella can also help prevent disease. Viral meningitis often resolves on its own.

Bacterial meningitis – This is the most severe form of meningitis. If not treated promptly, bacterial meningitis can lead to hearing loss, brain damage and death. The most likely pathogens are Haemophilus influenzae Type B, Neisseria meningitidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. It can be spread through direct contact such as coughing, sneezing or kissing an infected individual. Some forms of bacterial meningitis can even be spread through contaminated food that contains the Listeria bacterium. Examples of these are hot dogs, sandwich meats and soft cheeses. In addition to vaccination, a key prevention intervention you will hear repeated over and over again is to teach college students who live in dorms to avoid sharing utensils with others.

Fungal Meningitis – This is a rare form of meningitis that occurs when a fungus enters the blood stream and finds its way to the meninges. Individuals with a weakened immune system are most at risk and is most often caused by inhaling fungal spores from bird and bat droppings or contaminated soil. Fungal meningitis requires extensive courses of antifungal medication, usually administered in the inpatient setting via IV infusion.

Parasitic Meningitis – This is another rare form of meningitis and is usually fatal. It is caused by the parasite Naegleria fowleri, which enters the body through the nose, and the condition progresses rapidly over one to 12 days. The parasite lives worldwide in warm freshwater sources such as rivers, hot springs and lakes. It also lives in water heaters, inadequately treated swimming pools, industrial water runoff and soil. This form of meningitis is not transmissible person-to-person.

Non-infectious Meningitis – This is another form of non-transmissible meningitis. It usually occurs in correlation with conditions related to inflammation such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. It can also occur in cases of brain surgery, cancer, head injury and with the use of NSAIDS and certain antibiotics. Treatment is focused on the underlying cause and symptom management.

Pathophysiology

Most cases of meningitis are caused by an infectious agent that has colonized or established a localized infection elsewhere in the host.

The organism invades the submucosa at these sites by circumventing host defenses (eg, physical barriers, local immunity, and phagocytes or macrophages).

Invasion of the bloodstream and subsequent seeding is the most common mode of spread for most agents.

Meningeal seeding may also occur with a direct bacterial inoculation during trauma, neurosurgery, or instrumentation.

The blood-brain barrier can become disrupted; once bacteria or other organisms have found their way to the brain, they are somewhat isolated from the immune system and can spread.

When the body tries to fight the infection, the problem can worsen; blood vessels become leaky and allow fluid, WBCs, and other infection-fighting particles to enter the meninges and brain; this process, in turn, causes brain swelling and can eventually result in decreasing blood flow to parts of the brain, worsening the symptoms of infection.

Replicating bacteria, increasing numbers of inflammatory cells, cytokine-induced disruptions in membrane transport, and increased vascular and membrane permeability perpetuate the infectious process in bacterial meningitis.

Statistics and Incidences

The incidence of meningitis varies according to the specific etiologic agent, as well as in conjunction with a nation’s medical resources.

Only about 44% of adults with bacterial meningitis exhibit the classic triad of fever, headache, and neck stiffness.

Assessment

Fever: The patient presents with a fever at first, which ultimately gets worse.

Seizures. As bacterial meningitis progresses, patients of any age may have seizures (30% of adults and children; 40% of newborns and infants).

Neck stiffness :The patient feels stiffness in the neck as part of the triad of symptoms.

Positive Kernig’s sign. When the patient is lying with the thigh flexed on the abdomen, the leg cannot be completely extended.

Positive Brudzinski’s sign :When the patient’s neck is flexed, flexion of the knees and hips is produced; when the lower extremity of one side is passively flexed, a similar movement is seen in the opposite extremity.

Neurologic symptoms :Patients with subacute bacterial meningitis and most patients with viral meningitis present with neurologic symptoms developing over 1-7 days.

High-pitched cry. Infants may present with high-pitched crying.

Lethargy. An infant may appear only to be slow or inactive, or be irritable.

Photalgia (photophobia). Discomfort when the patient looks into bright lights.

The diagnostic tests in patients with clinical findings of meningitis are as follows:

Lumbar puncture. In general, whenever the diagnosis of meningitis is strongly considered, a lumbar puncture should be promptly performed; an examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is the cornerstone of the diagnosis.

CT scan. A screening computed tomography (CT) scan of the head may be performed before LP to determine the risk of herniation.

Blood studies. In patients with bacterial meningitis, a complete blood count (CBC) with differential will demonstrate polymorphonuclear leukocytosis with a left shift.

Chest radiography. As many as 50% of patients with pneumococcal meningitis also have evidence of pneumonia on initial chest radiography.

Cultures and bacterial antigen testing. The utility of cultures is most evident when LP is delayed until head imaging can rule out the risk of brain herniation, in which case antimicrobial therapy is rightfully initiated before CSF samples can be obtained.

Serum procalcitonin testing. increasing data suggest that serum procalcitonin (PCT) levels can be used as a guide to distinguish between bacterial and aseptic meningitis in children.

Medical Management

Bacterial Meningitis Precautions

It’s important to follow strict infection control protocols to prevent the spread of bacterial meningitis in healthcare settings. Some of the key precautions include:

Hand hygiene: Wash your hands frequently and thoroughly with soap and water or use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer before and after patient care.

Personal protective equipment (PPE): Bacterial meningitis requires droplet precautions. Use appropriate PPE, and utilize gloves, gown, mask, and eye protection, when caring for patients with suspected or confirmed bacterial meningitis.

Isolation precautions: Droplet precautions are used to prevent the spread of pathogens that are passed through respiratory secretions during talking, coughing, and sneezing. The droplets are large particles that travel about three feet through the air.

Environmental cleaning: Clean and disinfect surfaces and equipment in patient care areas to prevent the spread of bacteria.

Vaccination: Get vaccinated against bacterial meningitis and to promote vaccination to patients and their families.

Surveillance and reporting: Be vigilant for signs and symptoms of bacterial meningitis and to report any suspected cases to the appropriate authorities for prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Crystalloid infusion. If the patient is in shock or hypotensive, crystalloid should be infused until euvolemia is achieved.

Seizure precautions. If the patient’s mental status is altered, seizure precautions should be considered, seizures should be treated according to the usual protocol, and airway protection should be considered.

IVT and oxygen administration. If the patient is alert and in stable condition with normal vital signs, oxygen should be administered, intravenous (IV) access established, and rapid transport to the emergency department (ED) initiated.

Pharmacologic Management

Begin empiric antibiotic coverage according to age and presence of overriding physical conditions.

Sulfonamides. Trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole work together to inhibit bacterial synthesis of tetrahydrofolic acid.

Tetracyclines. Tetracyclines inhibit protein synthesis and, therefore, bacterial growth by binding with 30S and possibly 50S ribosomal subunits of susceptible bacteria.

Carbapenems. Carbapenems inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis by binding to penicillin-binding proteins; carbapenems, including meropenem, can be used for the treatment of meningitis.

Fluoroquinolones. Fluoroquinolones inhibit bacterial DNA synthesis and, consequently, growth by inhibiting DNA gyrase and topoisomerases, which are required for replication, transcription, and translation of genetic material.

Glycopeptides. Vancomycin inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis by blocking glycopeptide polymerization; it is indicated for many infections caused by gram-positive bacteria.

Aminoglycosides. Aminoglycosides primarily act by binding to 16S ribosomal RNA within the 30S ribosomal subunit; they have mainly bactericidal activity against susceptible aerobic gram-negative bacilli.

Cephalosporins, 3rd generation. Third-generation cephalosporins are less active against gram-positive organisms than first-generation cephalosporins are; they are highly active against Enterobacteriaceae, Neisseria, and H influenzae.

Antivirals. Antiviral agents interfere with viral replication; they weaken or abolish viral activity; they can be used in viral meningitis.

Systematic antifungals. Antifungal agents are used in the management of infectious diseases caused by fungi.

Vaccines, inactivated. Inactivated bacterial vaccines are used to induce active immunity against pathogens responsible for meningitis.

Corticosteroids. The use of steroids has been shown to improve overall outcome for patients with certain types of bacterial meningitis, such as H influenzae, tuberculous, and pneumococcal meningitis.

Osmotic diuretics. Mannitol may reduce subarachnoid-space pressure by creating an osmotic gradient between CSF in the arachnoid space and plasma.

Loop diuretics. Furosemide is a loop diuretic that increases the excretion of water by interfering with the chloride-binding cotransport system, which, in turn, inhibits sodium and chloride reabsorption in the ascending loop of Henle and distal renal tubule.